YOU may never have heard of FANUC, the world’s largest maker of industrial robots. But the chances are that you own a product built by one of its 400,000 machines. Established in 1956, the Japanese company’s automated workers build cars for Ford and Tesla, and metal iPhone cases for Apple. The firm distinguishes itself from competitors by the colour of its robots’ whizzing mechanical arms, which are painted bright yellow. Its factories, offices and employee uniforms all share the same hue.

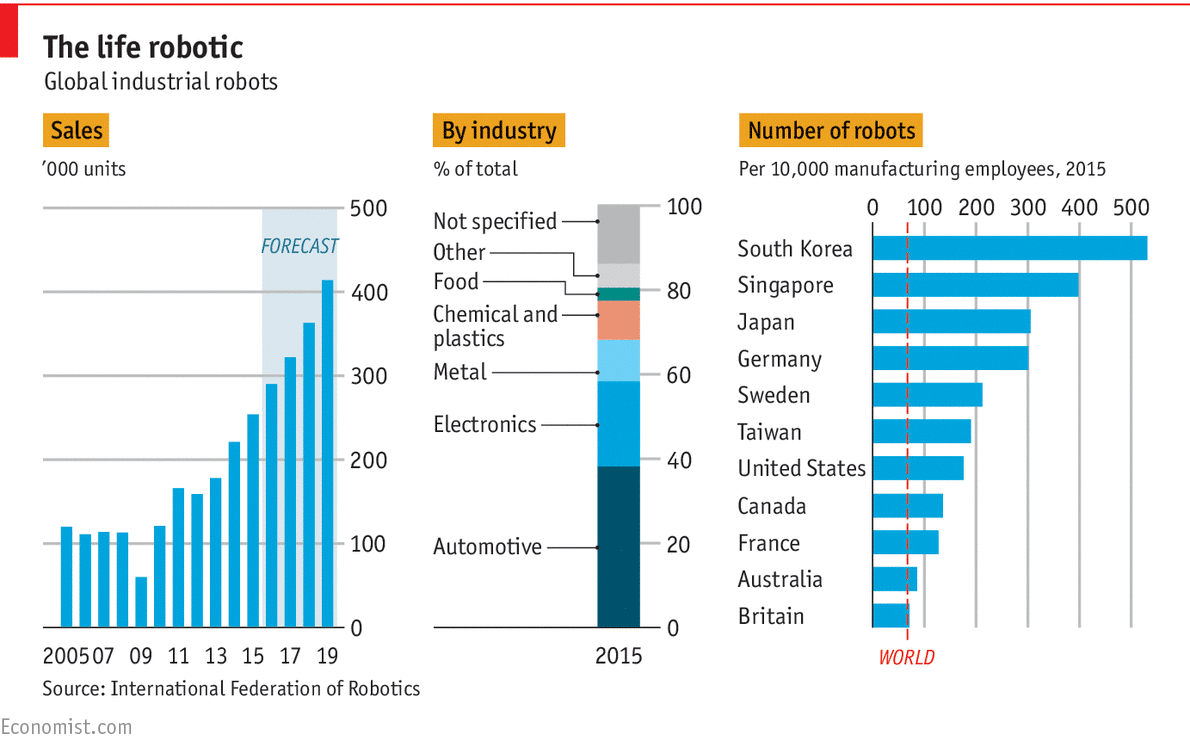

FANUC is red-hot at the moment. Its shares have jumped 35% in the past six months, more than double the 14% return of Japan’s benchmark Nikkei stock index. And the booming market for robots shows little sign of slowing. According to the International Federation of Robotics, unit sales of industrial robots grew 15% in 2015, while revenues increased 9% to $11bn. In 2016 turnover in North America rose by 14%, to $1.8bn. ABI Research, a consultancy, reckons that the industry′s sales will triple by 2025.

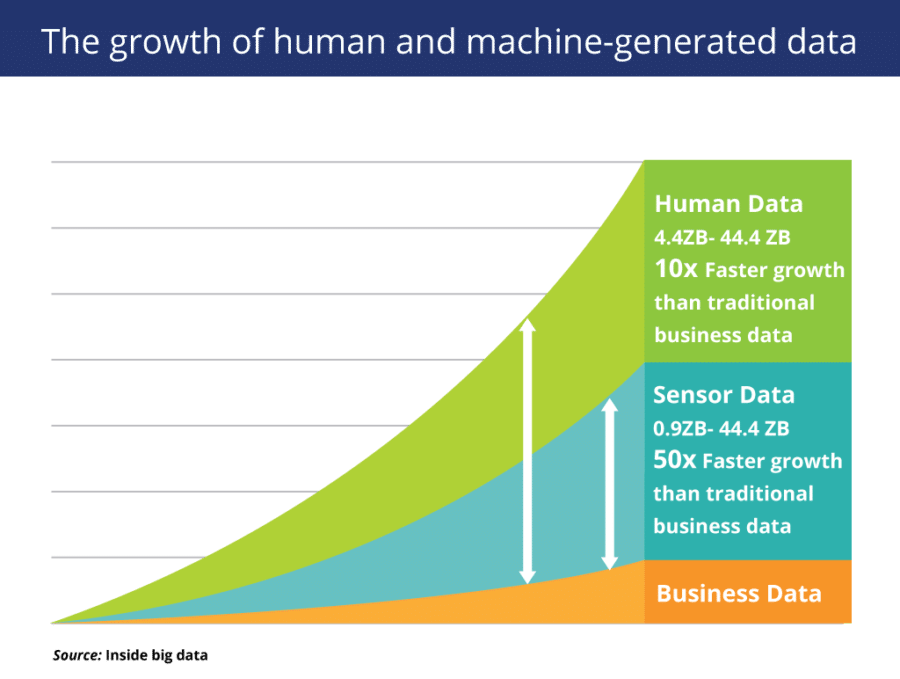

The popular narrative about robots is that they are stealing human workers′ jobs. A new paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research broadly supports this belief, estimating that each additional robot in the American economy reduces employment by 5.6 workers. However, the relationship between automation and employment is not always straightforward. One big trend is the growth of “collaborative robots”, smaller and more adaptable machines designed to work alongside humans. Barclays, a bank, thinks that between 2016 and 2020 sales of these machines will increase more than tenfold. Moreover, by improving productivity, automation can sometimes create new jobs for humans, or at least relocate them. Adopting robots has made it economical for some manufacturers in high-wage countries to “re-shore” production from poorer countries. This year Adidas, a sportswear firm, will begin producing running shoes in a German factory staffed by robots and 160 new workers.

FANUC is not taking its dominance for granted. The company is working on smarter, more-customisable robots and investing heavily in artificial intelligence. Its efforts to adapt in the rapidly evolving robotics industry can be seen even in the firm’s new choice of colours. When the company unveiled its first collaborative robot, CR-35iA, its trademark yellow colour had been replaced with green.

Original article here.